Kate Manne’s Unshrinking is a book about fatphobia. I’m going to review it. I discuss what the book has to say about health and fatness, and dieting, and some of the moral issues, then I highlight some of my criticisms. The tl;dr: I liked it and would recommend it.

Manne is a philosopher who also wrote Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny, which had a novel and interesting thesis, and Entitled, which I stopped reading because it felt like just a list of facts about male privilege, and I wasn’t learning anything new.

Unshrinking has some of that same journalistic energy as Entitled, by which I mean Manne has clearly done lots of research on this issue and a lot of the book is her synthesising and repackaging this research. In this case what made it work for me is I had a lot of ignorance or misconceptions around fatness, so the basic reporting of the book still met a need for me.

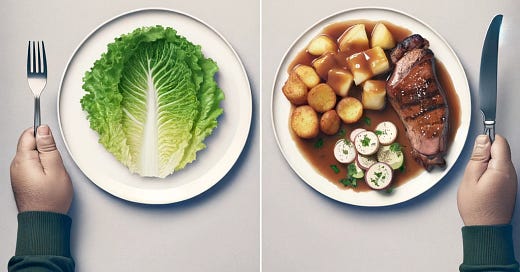

So what did I learn? A much better understanding of the health issues around fatness and dieting. Manne argues against the idea that fatness qua fatness causes poor health. While agreeing that being fatter [1] is linked with worse health, she points out that this is also true of being too lightweight, and that there’s some evidence that slightly overweight people have better mortality outcomes than ‘normal’ people. More to the point, she argues that many of the poor health outcomes associated with fatness arise from how our society treats fat people: fat people are less likely to go to the doctor, at the doctor they are less likely to be correctly diagnosed, and they may be less likely to exercise due to social condemnation and ridicule. These are all ways in which being fat ‘causes’ worse health, but mediated by fatphobia, not fatness per se. The best way to improve health for fat people would be to stop treating them worse.

Oh, and dieting? It basically doesn’t work, if ‘work’ means that a fat person can lose weight and maintain that loss. Because of genetic factors, but also the body’s establishment of a ‘set point’ weight, for most fat people it’s nigh impossible to permanently lose weight. People can lose weight, but then they regain it, and this ‘weight-cycling’ is definitely unhealthy, more so than simply remaining at a stable, elevated weight. It makes sense that it’s hard to achieve permanent weight loss: presumably fat people are very motivated to lose weight. It stands to reason that, if they are still fat, it’s a hard situation to change.

(After I finished the book I learnt from a friend of mine that he used to be very fat. Through a gargantuan effort of will he managed to shed tens of kilos. Years later, he still feels hungry every day.)

Manne also engages with moral questions around fatness and fatphobia. She posits that fatphobia is veiled classism and/or racism: a way for woke middle-class people to look down at lower-class people, to act out their repressed classism. I gotta say, this point struck me, as something that many have been guilty of, and many still are. She also questions moral judgements of fat people, eg., for the extra burden they place on the health system, arguing in effect that there is a double standard in place that is about fatphobia, not some fair-minded criterion.

The book is weaker in its discussion of appetite suppressant drugs like Ozempic/semaglutide. Manne says that the choice of whether to use these drugs should be personal, but she argues against it. I found this unconvincing. My understanding is that these drugs are an unalloyed good that can improve quality of life for many people. While they are currently expensive and out of reach, we should be trying to address this by making them cheap and accessible. It felt a bit like all the news around Ozempic was happening when Manne was already well through writing her book, and also that Ozempic undermines some of Manne’s thesis (what if it wasn’t hard to lose weight?), so it got a cursory and dismissive treatment.

My other criticism is a bit pedantic: Manne’s theses could be much clearer. Each chapter has an ambiguous title, and then Manne tends to meander a bit before getting to her thesis near the end of the chapter. I really valued the autobiographical details and Manne’s introspection on her own fatness; I would have liked it even more if chapters had titles like “Dieting is ineffective and bad for your health” with opening sentences like “In this chapter I explore how dieting is not an effective method of losing weight, and can in fact worsen health outcomes.” The internet tells me that Manne draws on analytic philosophy, I imagine Manne is capable of writing in such a fashion, so I suspect this was an editorial choice to make the book feel less like philosophy and more like popular science. In the end it does a disservice to Manne’s argumentation.

For me, the marks of a good non-fiction book are things like: I keep thinking about it after I finish it, it influences how I think, it leads to interesting conversations with others. Unshrinking meets this bar. It’s changed how I think about fatness and fatphobia, and given me a greater insight, albeit necessarily limited, into the situation facing fat people.

[1] Manne avoids medical descriptors like ‘obese’, as well as terms like ‘overweight’ which imply an excess relative to some ideal. She uses fat throughout her book as a more neutral descriptor, a convention which I hope to adopt and maintain.